National Comics Publications, Inc. v. Fawcett Publications, Inc.

Writers should know that ideas can’t be copyrighted, only the tangible expression of those ideas.

The words of a story. The notes of a song. The lines of a drawing. If those are substantially similar in the eyes of a court, that’s infringement. If not, it’s a different expression of (perhaps) the same idea. Pursuing an infringement case is not automatic. You have to prove it in a court (which can be expensive and time-consuming) or credibly threaten to prove it so the other party backs down.

This is one of the most fundamental and the most misunderstood concepts in copyright law. (It’s right up there with people confusing copyrights, trademarks, and patents.) People think ideas can be copyrighted. They can’t.

And then there’s National Comics Publications, Inc. v. Fawcett Publications, Inc.…

National Comics published a character called Superman. You may have heard of him?

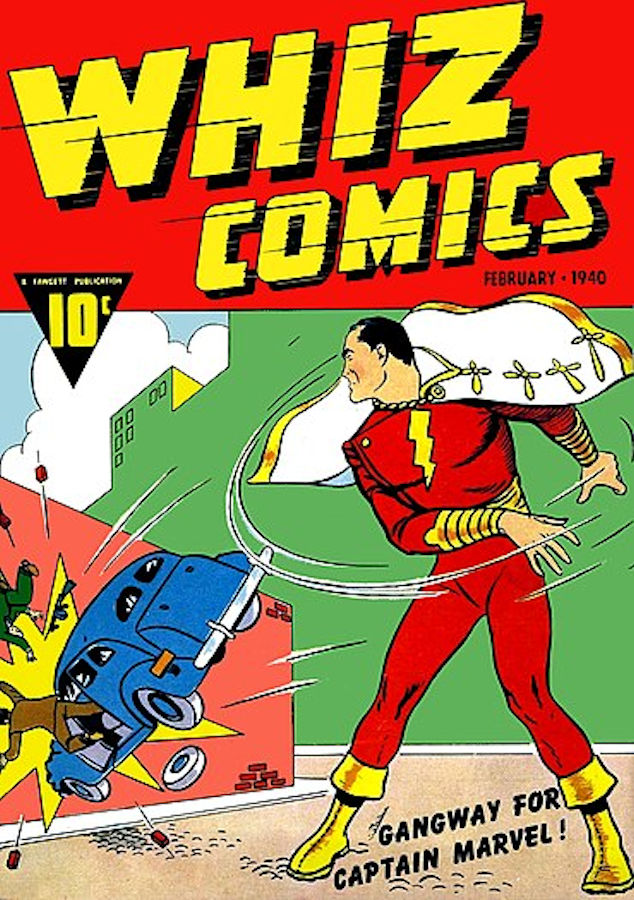

Fawcett published a character called Captain Marvel. You may have heard of him; or you may have heard of one of at least two other characters with the same name. Or you may know him under his new, thoroughly confusing name: Shazam.

It’s really difficult to look at Captain Marvel and not conclude that he was… let’s say “inspired by” Superman. Strong, nigh invulnerable superhero in a cape is a common trope today, but it was still new then.

But National didn’t allege “inspired by”, which isn’t against the law; they alleged copyright infringement, because Captain Marvel performed some of the same super feats as Superman.

Fawcett responded in part not by denying the claims, but by denying that copyright existed. Today copyright exists as soon as a work is created. Back then, copyright only existed after registration; and past a certain date, it had to be renewed. (Witness the image with this article: it’s the cover of Whiz Comics #2, which Fawcett failed to renew, and hence it’s now public domain.) Fawcett argued that since National had failed to renew copyright for their newspaper strips, there was no copyright. The judge ruled that since they had registered the comics, the comics were copyrighted while the newspaper strips weren’t. I wonder if this tactic backfired on Fawcett, because it implicitly conceded that copyright was a valid concern in the case. In hindsight, I might have argued that copyright did not apply.

I haven’t looked at the visual evidence. It’s entirely possible that some of Cap’s pictures were copied from Superman’s. It’s a long, venerable comics tradition called “swipes”: an artist admires another’s work and tries to copy it and learn it — or just copy it to meet a deadline. It’s probably copyright infringement if you want to press it, but it’s pretty common. Such a claim would require a court to look at the works side by side and make a judgment call.

But “the same super feats”? That sounds like we’re back to ideas. And ideas can’t be copyrighted, only the specific expression of an idea.

Note that I have carefully avoided saying “the specific words”, even though that’s common phrasing when discussing copyright of printed works. It’s relatively easy to judge when words are infringed: when substantially the same words appear in substantially the same order without significant alterations (and it’s a significant subset of the original work), that’s infringement.

I’m avoiding that phrase because I believe you can argue that comic books are a visual medium, and their expression is a particular combination of words, pictures, and panel layouts. These are the language of comics. It’s more visual judgment than just text.

So leaping tall buildings in a single bound is an idea, not an expression; but copying a particular series of panels and words that show the hero leaping a tall building might be an infringement.

It’s sometimes said that Captain Marvel was found to be an infringement, but that’s a superficial and ultimately inaccurate reading. What actually happened was the Court of Appeals ruled that it was possible that these elements were infringing, and so sent the case back to the lower court for retrial; and Fawcett threw in the towel. Superhero book sales were in decline at that point. Trying the case (and possibly losing) would cost a lot to gain a little. They settled out of court, and they got out of the superhero business. And decades later, National (now DC) first licensed and then bought all the Fawcett characters and stories — including Captain Marvel.

My opinion? I can’t have an informed opinion without seeing the evidence, but I think Fawcett probably took their inspiration from Superman, then took the character in very different directions. I suspect National saw the character’s success and decided that suing was easier than competing.

But though this might seem on the surface to be a case of copyrighting ideas, it’s more complicated. And more fascinating to a comic book nerd.